A River of Time, a Warehouse of Cultures

Encountering 5 objects of Rhinelandian origin at a visit to the new V&A East Storehouse, London – and a quiet question mark. By Charlotte Desaga

In the East London’s Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, a new institution is reimagining the very soul of the museum. The V&A East Storehouse, built within the former London 2012 Olympics Media Centre, represents a radical departure from traditional museum practice. Part of the Victoria and Albert Museum – Britain’s world-renowned repository of art, design, and decorative objects spanning 5,000 years – this new space is far more than a storage facility. It is a bold declaration on the future of cultural heritage, where the public can access and interact with museum collections in ways previously unimaginable. Designed by the New York firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro, renowned for sculpting the iconic NYC High Line, in partnership with the UK’s own Austin-Smith:Lord, the Storehouse heralds a paradigm shift. It advocates the idea of radical transparency and immersive public access, trading traditional curation for a direct, unfiltered encounter with history.

At its core beats the heart of „curated transgression,“ a philosophy promoted by architect Liz Diller. She envisions the Storehouse not as a static archive, but as a „shapeshifting joy,“ a cultural „superstore“ where visitors become curators of their own experience. Here, you can „twist the kaleidoscope,“ as Diller puts it, and „sample a little bit of everything,“ breathing the same air as the artifacts themselves. It is a visceral, unmediated communion with history, a world away from the sanitized, glass-encased displays of traditional museums. You can wander through aisles overflowing with treasures, from ancient relics to cutting-edge design, all within reach.

This revolutionary concept demanded a complete reimagining of museum architecture. The traditional model – public galleries at the forefront, private storage hidden from view – has been inverted. Here, the public is thrust into the very heart of the collection, while the vital work of conservation and research unfolds on the periphery, still visible, still part of the living story. This is no mere architectural sleight of hand; it is a declaration of the people’s right to its shared heritage.

The sheer scale of the place is breathtaking. At 16,000 square meters the Storehouse hosts 250,000 artefacts, 350,000 books, 1,000 archives, a dizzying accumulation of human ingenuity spanning millennia. To immerse yourself in this space is to feel the weight and wonder of history, to sense the millions of stories whispering from every shelf. It is a place where ideas, beliefs, sorrows, and joys converge, a metaphysical whirlwind that leaves the mind spinning with possibility once you allow yourself to get immersed by the atmosphere each object is subtly extruding.

The architectural heart of the Storehouse is the Weston Collections Hall, a dramatic, 20-meter-high central void. This is where the journey begins, a grand stage for the unfolding drama of the collection. From here, a network of walkways, platforms, and viewing galleries invites exploration, offering ever-changing perspectives on the treasures within. A glass floor provides glimpses into the bustling world of the level below, a constant reminder of the life and energy that permeate this extraordinary place.

„Hacked“ storage racks transform industrial shelving into miniature curated displays, offering glimpses into the V&A’s vast and varied holdings. The walkways that crisscross the central hall echo the width of the iconic „streets in the sky“ from the in 2017 demolished Robin Hood Gardens housing estate, a fragment of which is poignantly preserved within the Storehouse – provides a link to the local London community and its latest history (a panoramic video piece by South Korean artist Do Ho Suh, on view at Tate Modern until October 26th, beautifully explores the legacy of this landmark further). Glass panels offer a window into the meticulous world of the conservation labs, where visitors can witness the skill and dedication that go into preserving our shared heritage. The entire space is bathed in a soft, artificial top-light, a necessity for conservation that also serves to focus the visitor’s attention on the objects themselves, each one a star in this extensive constellation of the human need for expression. In an era of ever-increasing public engagement, V&A East Storehouse offers a compelling blueprint for how cultural institutions can open their doors and share their treasures with the world. Its design, using the raw, industrial beauty of the warehouse, is both a pragmatic solution to the challenge of storing a vast collection and a powerful symbol of a more open, and less hierarchical approach to cultural heritage.

And then there is the masterstroke: the „Order an Object“ service. With a few clicks, anyone, anywhere in the world, can browse the V&A collection online, select up to five objects, and arrange a private viewing at the Storehouse. It is a simple, revolutionary act that transforms the visitor from a passive observer into an active participant in the life of the museum. To hold a piece of history in your hands, to examine it up close, is to understand in a profound way that this heritage belongs to us all and that the state we are in is resulting from it.

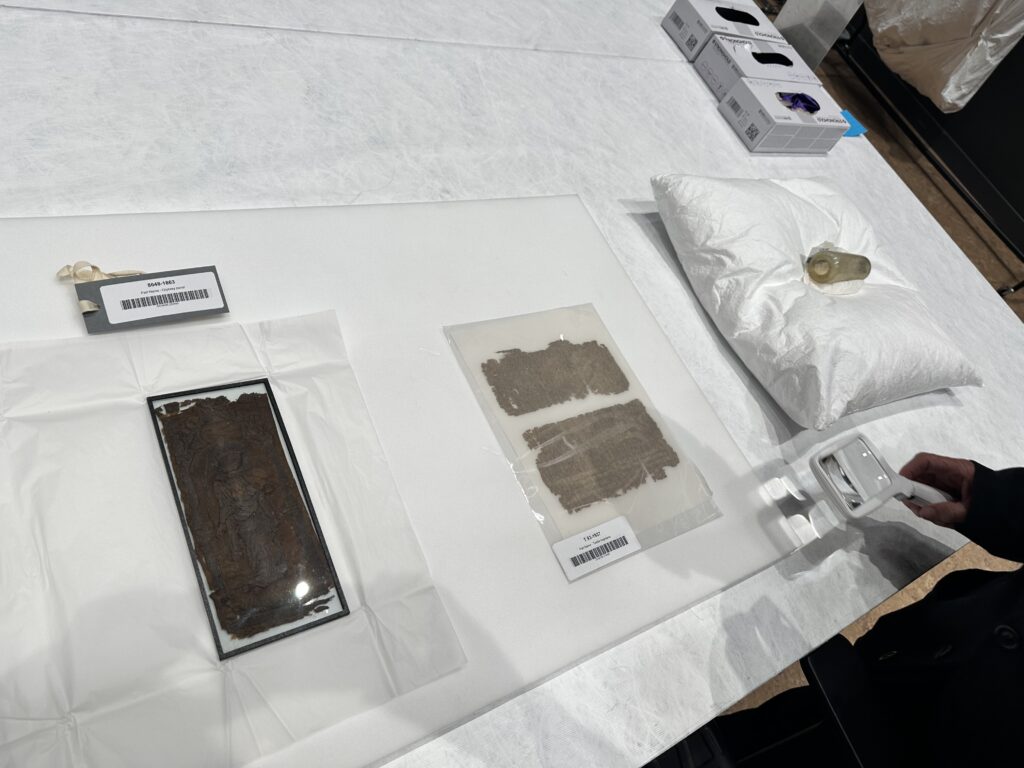

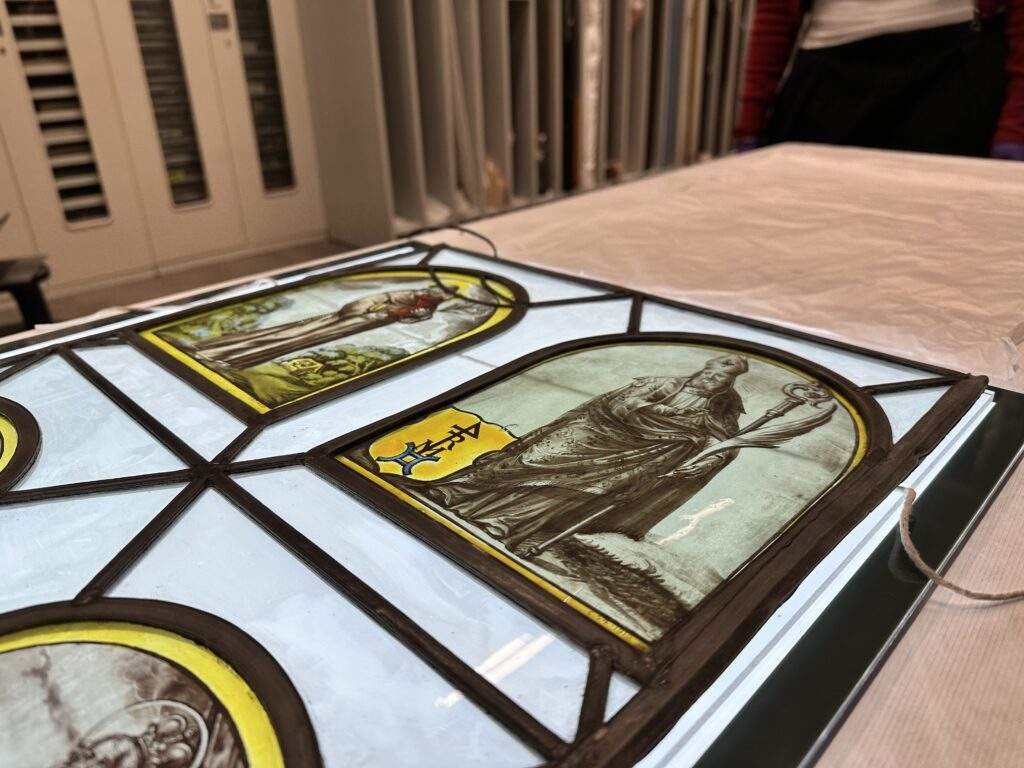

My order: A Roman glass jar, a Byzantine silk textile, a medieval embroidered panel, a Renaissance stained-glass window, and a 19th-century Romantic landscape painting. At first glance, a disparate collection of objects, bound by little more than the passage of time. But these five artifacts, all hailing from the German Rhineland, tell a story – a sweeping, epic tale of a European crossroads, a river of time that has carried with it the currents of trade, faith, and artistic spirit. Presented on a simple white table in the museums viewing room, armed with a magnifying glass, the first impression is one of awe. These are not mere objects; they are survivors, emissaries from a distant past.

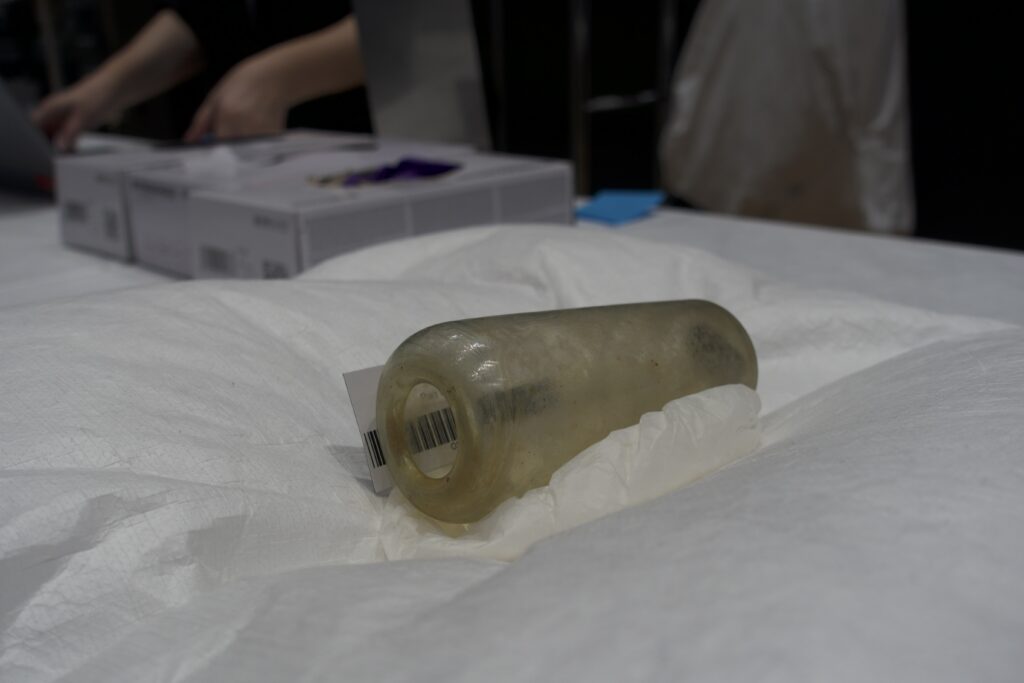

Our journey begins in the Roman era, with the humble glass jar from the late 3rd to 4th century. Forged in the fires of Cologne, a city born from the Roman settlement of Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, this small vessel speaks volumes about the Rhineland’s role as a vital frontier of the Roman Empire. One cannot help but wonder at the generations of hands that have cared for this fragile little object, ensuring its survival through the long march of history. Cologne was no mere military outpost; it was a bustling hub of commerce and industry, famed for its exquisite glass. This jar, a testament to the skill of Roman artisans, is a tangible link to the very foundations of Rhineland culture, a region forged in the crucible of Roman civilization and Germanic tradition.

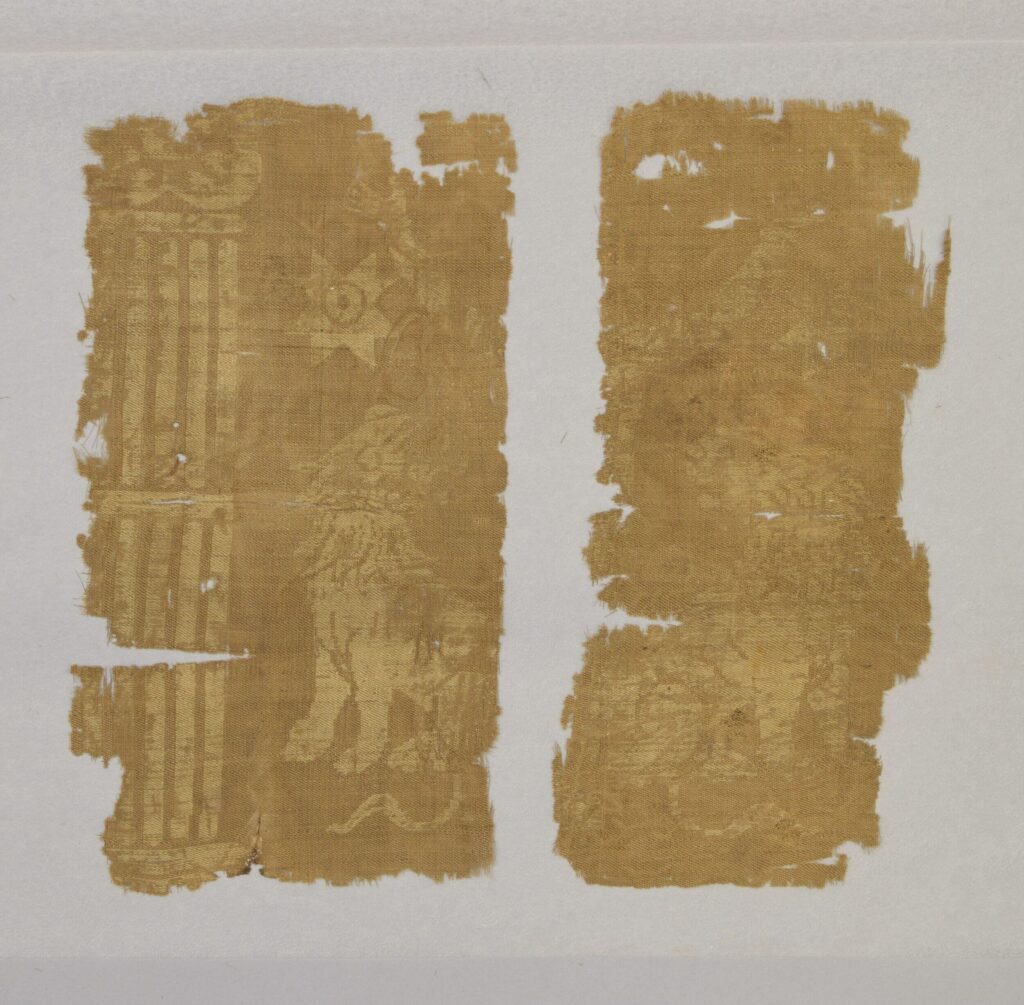

Centuries later, the Rhineland’s pulse still beat strong, a vital artery of trade and cultural exchange. A fragment of Byzantine-style silk from the 8th-10th century, discovered in a Rhenish church, tells of the far-flung trade routes that connected this region to the glittering heart of the Byzantine Empire and the fabled Silk Road. Though time has frayed its edges, the luxurious echo of this precious samite, depicting Daniel in the lions‘ den, remains. Its presence in a Rhineland church speaks to the wealth and influence of the region’s ecclesiastical institutions, which were not only centres of faith but also important patrons of the arts. This legacy is further illuminated by an exquisite 14th-century orphrey panel (a panel worn by priests, containing gold and silver threads), a beautiful piece from the renowned embroidery guilds of Cologne. This small but precious fragment, depicting St. Ursula, the beloved local saint, showcases the extraordinary skill of the city’s artisans and the profound piety that infused medieval Rhineland society. Time has entirely muted its colors, leaving behind a monochromatic dark brown tapestry of accurately placed stitches. It turned into a minimalist echo of its former glory but now draws even more attention to each single stitch.

Finally, we arrive in the 19th century, in the company of Johann Wilhelm Lindlar’s painting, „A Mountain Torrent“ This sublime landscape, painted in the 1860s and a product of the Düsseldorf School of painting, ushers in a new chapter in the Rhineland’s cultural story. In the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, the region became a crucible of German nationalism and the Romantic movement. Artists and writers flocked to its dramatic landscapes, medieval castles, and rich folklore. Lindlar’s painting, with its depiction of nature’s untamed power, is probably not the most exquisite but still an interesting example of the Romantic spirit of that time and place.

The 17th-century stained-glass panel of St. Michael overcoming Satan, also from Cologne, plunges us into a period of profound religious and political turmoil. The dramatic depiction of the archangel, a potent symbol of the Catholic faith, reflects the fierce conflicts of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. That this glass panel was torn from its original setting is a poignant reminder of the iconoclasm and destruction that swept through the region during this turbulent era. And yet, its survival is a testament to the enduring power of faith and the resilience of the Rhineland’s artistic spirit.

These five objects, spanning nearly two millennia, reveal the Rhineland as a cultural river, its currents carrying ideas, beliefs, and artistic traditions across the vast expanse of time. From the practical craftsmanship of Roman glassmakers to the mystical visions of Byzantine silk weavers, from the devout artistry of medieval embroiderers to the dramatic spirituality of Renaissance glaziers, and finally to the sublime landscapes of Romantic painters, each object is a unique and precious facet of the Rhineland’s ever-evolving history. These five objects, now resting in the fantastic sanctuary of the V&A East Storehouse, reminding us that cultural heritage is not a static monument, but a living, breathing entity, forever flowing and evolving like the great river that gave this region its name.

Postscriptum: A Ghost in the Machine

The article above was already complete when a final, insistent thought emerged – one that doesn’t quite fit the celebratory narrative.

In the very first millisecond that the museum’s grand interior revealed itself to me in all its epic dimension, I felt the fleeting, spectral touch of déjà vu. Why did this vast, unfolding vista feel so uncannily familiar? And then it struck me with the force of an epiphany: it reminded me of photographs of an Amazon warehouse. Those sweeping, panoramic shots of colossal industrial shelves, where hundreds of thousands of goods lie in wait, ready to be ordered and consumed by hundreds of thousands of individuals, each item destined for a personal, self-selected purpose.

This comparison, once it took root, refused to be shaken. The V&A East, in its laudable and ambitious mission to democratize access, seems to inadvertently echo the logic of the digital marketplace. It presents a seemingly infinite catalogue of cultural ‚goods,‘ and its brilliant „Order an Object“ service, for all its revolutionary appeal, positions the visitor as a consumer, browsing a celestial menu of history and art. We are invited to become the architects of our own experience, to follow the whims of our curiosity. But is this true intellectual freedom, or merely the illusion of it, played out within a vast, albeit beautiful, warehouse?

This raises a crucial question, a ghost in this magnificent machine: when we dispense entirely with the guiding hand of the curator, do we risk losing something essential to the expansion of our own horizons? Curation is far more than mere selection; it is an act of intellectual and narrative construction. Curators introduce us to subjects we didn’t know we were interested in, pushing us into unfamiliar intellectual and aesthetic territory.

The greatest moments of learning that broaden our understanding of the world, rarely occur within the comfortable, well-lit aisles of our existing interests. They happen when we are confronted with a perspective that is not our own.

The V&A East’s model is a necessary antidote to the elitism that has long haunted the museum world. But in its radical embrace of the individual, does it inadvertently champion a form of cultural consumerism? Does the ’superstore‘ of culture, where every choice is our own, ultimately limit us? Do we risk creating an echo chamber of personal taste, endlessly reinforcing our own biases, rather than being challenged by a vision greater than our own?

A quiet but persistent question mark hanging in the air of this remarkable space, a reminder that the path to true knowledge is not always a matter of personal selection. Sometimes, the most rewarding journey is the one we are guided on, a path that leads us to destinations we never knew we were looking for.

Article image: Charlotte Desaga