Sometime there’ll be art and nobody will see it

/ DE /

Speculations on art and its dissolving. An essay by Noemi Smolik

Of late, the concept of speculative materialism/realism has been making the rounds in philosophy and art. In brief, according to proponents of this new form of thought the world can and must be conceived independently of humanity. Kassels’ Fridericianum explored the relevance of these approaches in contemporary art, through the summer of this year holding three events accompanied by a conference and artist conversations. This large-scale trilogy did not escape the attention of art criticism: many reviews were published and there was a great deal of discussion. But in most reviews, the still young approaches and their influence upon art were met with mockery and ridicule. This is hardly surprising, being the standard tactic of the eternal conservative against the new. Many of the 50 artists of a so-called “post-internet” art generation represented in the exhibitions refer to speculative realism. This is reason enough to explore the link between this philosophical current and several contemporary trends in art in light of these three exhibitions.

“Speculations on Anonymous Materials”, Installationsansicht Fridericianum © Photo: Achim Hatzius / Vorne: Oliver Laric, 5, 2013, HD video 10’00’’, Courtesy Oliver Laric, Seventeen, London and Tanya Leighton, Berlin / Hinten (v.l.n.r..): Alisa Baremboym, Syphon Solutions, 2013; Travel Impression, 2013; 6-D, 2013; Sterile Impression, 2013; James Richards, The Screen, 2013

With the first show “Speculations on Anonymous Materials” the decisive terms were of aesthetic debate were already on the program. In traditional, dialectical terms, speculation and material contradict one another, since speculation refers to thinking about infinity and the absolute, in other words, what transcends the material. In contrast, the material is part of the hard facts of physics. Since the new speculative materialists/realists have come along, everything seems different.

Given experimental science’s ability to provide information on a world prior to the emergence of organic life, what existed before thought, materialism should no longer exclude speculative thought, as French philosopher Quentin Meillassoux argues in his book After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency (2008). He also promotes the suspension of finitude and argues that there is no necessity, but that anything could happen, but need not to.

“Speculations on Anonymous Materials”, Installationsansicht Fridericianum © Photo: Achim Hatzius / Vorne: Katja Novitskova, Approximation V Chameleon, 2013, Digital print on aluminum dibond, cutout display, 145 x 130 x 20 cm, Courtesy Katja Novitskova und Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin / Hinten links: Ken Okiishi, gesture/data, 2013 / Hinten rechts: Katja Novitskova, Branching II, 2013

According to American thinker Graham Harman, who teaches at the American University of Cairo, the opposition, established ever since Kant, between subject and object, privileging the subject as the source of perception, needs to be rethought. He speaks of an object-based ontology that sees the object as equal in stature to the subject. If we consider the arrogance with which the Western subject confronts the rest of the object world, the post colonial world, the world of animals, the world of resources, this approach based on equal status could be liberating. But exactly how that should work is something that nobody knows exactly, as the French theorist of science Bruno Latour has been pointing out for many years now. He is generally considered the forerunner of this position. Something has already taken place in the understanding of the subject, since the line separating object and subject is becoming ever more permeable, as we can all experience in the world of the Internet.

If the title of the first exhibition referred to the anonymous origin of computer-generated images and at the same time to the subversive actions of the Anonymous movement, the second exhibition “Nature after Nature” explored the materiality of the material. The third exhibition “Inhuman” ultimately looked at the future of humanity. For this third exhibition, the curator chose as a motto the text “The Inhuman” by Jean-Francois Lyotard, which explores the question—as it were in parallel to the question posed by Meillassoux of whether we can think about a world before thinking—whether it would be possible to think without bodies.

Timur Si-Qin, Axe Effect, 2013 (Ausschnitt) Installationsansicht “Speculations On Anonymous Materials”, Fridericianum, © Photo: Achim Hatzius, Courtesy Timur Si-Qin und Société, Berlin

Artists work with the body in all three exhibitions, but no longer with a view of the body as the origin of perception, as it was seen since Kant in a defined space-time continuum. Instead, here it was the object of purification, of stimulans, of an increase of perception—in brief, the object of optimization. The number of works that deal with pure mineral water, diverse bodily cleaning materials, or mood-enhancing materials was surprising. For example, Timur Si-Qin, who as a commentary to the heroic gesture of abstract expressionists issuing forth from the subject, skewered plastic bottles of the men shower gel AXE onto a Samurai sword and had the content run down to the floor in banal Pollockesque puddles.

If for modern art the subject was what stood opposite the world of objects, for the artists represented at Kassel the subject seems to become an object. For example in the high-definition film Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths (2013) by British artist Ed Atkins, that not only opposes the hyper reality of the animated human body to its filmed immateriality, but also asks what happens with language when it is spoken by computer-animated people. Does this language still communicate or is it mere information, like the display board at an airport, and does the human being then become code?

The bizarrely dressed hyperactive young people that constantly speak past one another in Ryan Trecartin’s disturbingly anarchistic film Item Falls from 2013 also seem like coded people. And while they debate over the possibility of allowing a computer-animated horse to appear, a real horse materializes in the room. Finally a subject that leaves the young people speechless, communication can begin.

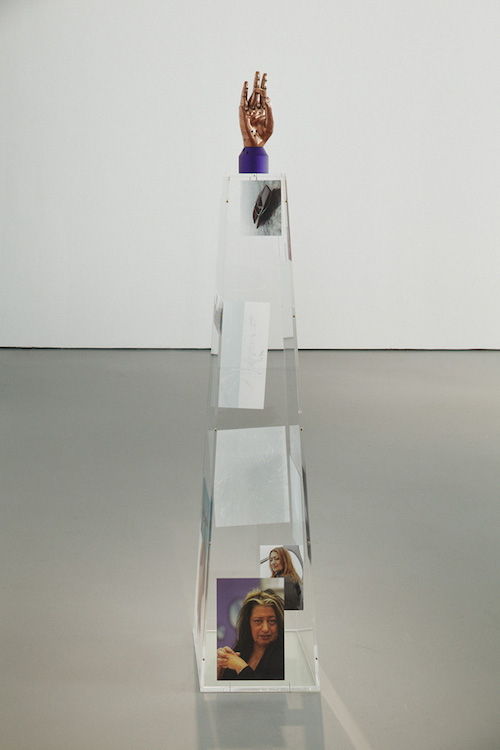

It is the hands that allow the subject access to the digital space via the touch screen. Josh Kline portrays his friends by capturing them in a 3D print holding their favorite objects in their hands, cans with stimulant drinks, soaps, and smartphones.

Alexandra Domanič born in Yugoslavia, used the 3D printing technique to reproduce the so-called Belgrade Hand, the first hand prosthesis with sensory capacities made in Yugoslavia in 1963. The hand as a bridge to the digital world. At the latest here, we begin to suspect what Graham Harman meant with an object-oriented ontology. We, our hands have long become part of the digital world of objects. In a post-post Marxist sense, this would be called alienation, today we call it de-subjectivation. This does not mean that the subject no longer plays a role. Only our relationship to the object world changes in a way that Bruno Latour tries so thrillingly to capture in his latest book Modes of Existence.

Aleksandra Domanović, Živa, 2013, © Foto: Achim Hatzius, Speculations On Anonymous Materials, Fridericianum

This tendency towards de-subjectivation is followed by a second that reveals itself in the exhibition series. Images that emerge from the inspiration power of the subject are no longer in demand. The source and origin of the pictures of almost all the artists represented in artist is a universe fed by information networks. The already existing, incidentally found, something that came the artist’s way is taken up, gathered, stored, without a conscious intervention of the subject and without certain criteria. This contradicts the classical foundation of modernism, which still assumed that the new can emerge from nothing. But was the new not always just a mutation of the existing and thus one of the greatest myths of modernism?

Instead of inventing the new, there is multiplication through mutation, overlapping, mixing and dividing. Here we should mention the animation video UterusMan (2013) by Shanghai-born artist Lu Yang which could be seen in the third part of the trilogy “inhuman.” Here, a kind of superman/woman takes on the contours of a uterus. Outfitted with this feminine superpower, he chases through a world of mangas and video games, filled with film sequences, Xrays images, and scientific photographs. He begets himself, producing monstrous babies and shoots his enemies with egg cells. All the lines separating feminine and masculine, human being and machine, nature and artificiality are suspended in this dimension. In the video Ohne Titel (2015) by Oliver Laric, women’s breasts transform into dog muzzles, trees into animals, animals into machines.

Shot from images and film scenes by various animation artists these subjects remain forever caught in the process of becoming, without beginning or end, without gender and identity.

The presence of so-called quasi objects up to their mischief, accelerated by the new technologies, has been described by Bruno Latour for a number of years now. He also points to the fact that through the emergence of such human-objects drawing a demarcation or distinction between nature and culture, human being and machine, material and speculation, finitude and infinity—the pillars of modern thought at the latest since Kant—is becoming ever more difficult.

And thus we find ourselves in another artistic development that reveals a paradox: a striking number of artists are working currently with invisible or immaterial materials like light, vapors, fluids, or magnetic and electric fields. This became clear above all in the second exhibition “Nature after Nature.” For example, Susanne M. Winterling shows a laboratory shot of a scorpion, that possesses the capacity, invisible to human eyes, to absorb blue light and to radiate it in other glowing colors, referring to the barely researched realm of color in the darkness of the sea.

Swedish artist Nina Canell (b. 1979) turns in her works toward the presence of air and odors. Her minimalistic sculpture Interiors (Condensed), a water glass with captured air on a bright carpet—created a relationship of tension between the limit of the glass and the air, between inside and outside.

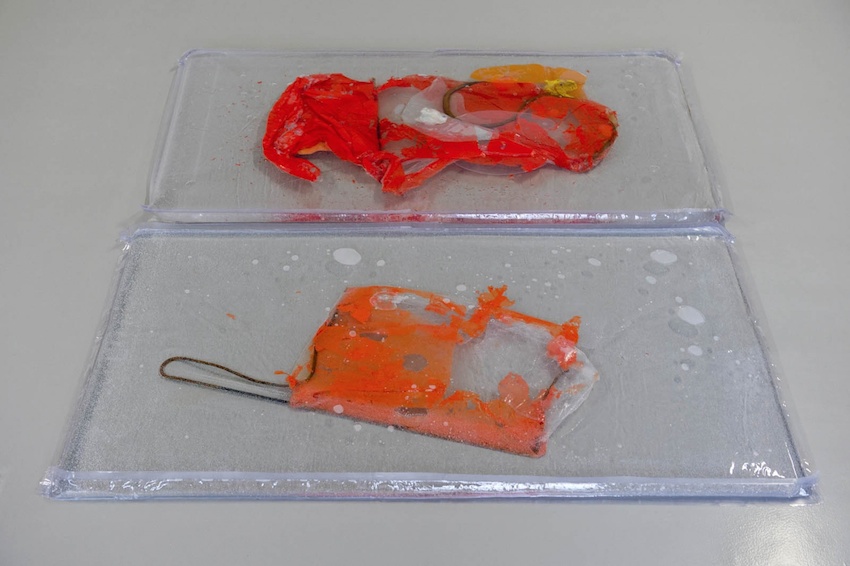

Ukrainian artist Olga Balema challenges time, by filling transparent plastic pillows with water and various materials that over time change their color and texture in an endless process through the mutual interaction of the materials.

All these materials are characterized by a fluid state that knows no limits. This leads the already mentioned artist Si-Qin, who paints with flowing showing gel, borrowing from Meillassoux, to speak of an aesthetic of contingency, which means something like a constant and unpredictable material flow within semi-stable structures.

The lines separating life and death, infinity and finitude seem to blur.

In her gripping video Hyperlinks or It Didn’t Happen from 2014, Cécile B. Evans (*1983), based in London and Berlin, asks about our own personal lives on line. The bad digital reproduction of the dead actor Philip Seymour-Hoffman, brought back to life to keep a blockbuster series going, is commented upon with a loose sequence of episodes of YouTube videos, photographs, and animation:

New forms of continuing life are treated by Aleksandra Domanovič in her work HeLA on Zhora’s coat, von 2015. She prints transparent raincoats with images of HeLa cells. Theses cells were extracted in 1951 from the cancer-patient Henrietta Lacks from Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. They are the first cells that were cultivated outside the human organism and are still used today as a foundation for further research. So despite her death Henrietta Lacks lives on in these cells, challenging our understanding of death. The more the new technologies saturate our lives, the more confusing the questions of the material and the immaterial, of death and immortality, finitude and infinity become. And yet these very technologies seek to draw clear leans between object and subject, life and death, matter and illusion.

But where everything flows together, as in the videos of Yang and Laric, where life after death continues in animated images and where artworks are located, as artist Si-Qin demands, in an unpredictable material flow, does this not place a trap for art? For if there are no longer any clear borders, then there are no longer any clear limits distinguishing the aesthetic object from all other objects. Then there is no longer art. Is that perhaps our future? “From the perspective of the now, the future of humanity seems monstrous,” according to the artist Julieta Aranda in the accompanying volume of the exhibition Inhuman, “but that need not mean something negative.” Exactly! Because where everything finds itself in a state of transformation, nothing or in fact everything could become art.

Top image: Susanne M. Winterling, Ecologies (microlevel solidarity lab), 2014 (Detail)