Peter Zimmermann

/ DE /

Painting versus Plasma Flatscreen – A Portrait by Harald Uhr.

For a change, why not talk a bit about continuities in the Rhineland? Along with all the perplexity, readjustments or jibes about rural exodus, there are in fact continuities too. Due to their constant ongoing and further development, these continuities naturally do not appear without their breaks or deviations or corrections, and they only come into focus now and then, but somehow much too rarely. Peter Zimmermann, for example, born in 1956 in Freiburg, has meanwhile been living and working in Cologne for over thirty years now. Immediately after finishing his studies at the Academy in Stuttgart, he found himself in the hot spot of current art events at that time. “Wilde Malerei” was just celebrating its triumphs there, and the necessary counter-movements were beginning to appear on the horizon, although not quite so loudly. After his training in the painting class with Paul Uwe Dreyer, however, Zimmermann did not join the ranks of boisterous, promising young men on the brink of success. Why should he, when in the same year Kasper König showed with a grand gesture in the Düsseldorf exhibition hall what kinds of alternatives there were here in the Rhineland. Even though the exhibition “Von hier aus” (“Starting From Here”) also treated, for instance, “The Problems of Mini-Golf in European Painting” in a cycle by Werner Büttner, there were also strict Conceptualists, Formalists, seekers, model builders, and all kinds of border-crossers alongside the father figure Beuys, who made a highly regarded appearance. The newly emerging context artists, on the other hand, who were to become the leaders for long stretches in the nineties, at least in Cologne, were largely ignored. The generational conflict between the boys’ painting of the eighties and the discourse art of the nineties was beginning to appear on the horizon, even if only dimly in the beginning.

It was specifically this Cologne art scene that served in the 80s/90s as a paradigm of a networked social structure, which also contributed, not least of all, to its glorified historicization. In retrospect, the circumstances could be read, for instance in an article by Dominikus Müller, as follows: “From the present perspective of the constant economicization of relationships and identities, the 1990s in Cologne appear most of all as a time, in which acting in networks and working on oneself could still be regarded in a positive sense as a (presumably) leftist, emancipatory and, most of all, self-determined project.”

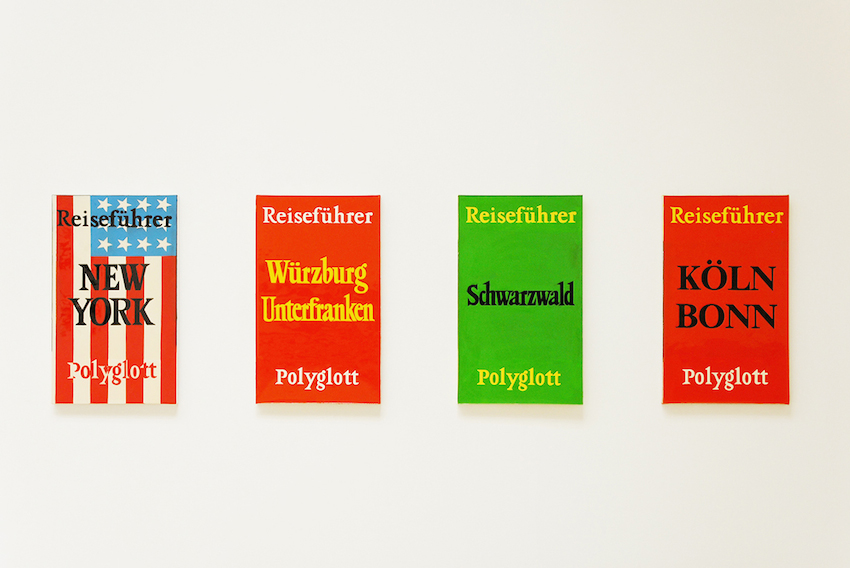

To a certain extent Zimmermann entered into these networked structures in the beginning and also quickly became accepted in the coolly arguing discourse circle in the new galleries, such as Christian Nagel, Esther Schipper or Tanja Grunert, where the operating system of art was put to the test, and kindred spirits from places like Vienna, Munich or New York were soon at hand. Despite the sometimes sparse installations and linguistic distractions, which an initially perplexed, because uninitiated, audience encountered in the galleries, sublime painting was not neglected either, at least as an area of friction. It was just hung a bit lower and questioned about its obsolete claim to sophistication. In the late eighties Zimmermann therefore exhibited his book cover paintings in the charming backstreet gallery rooms of Tanja Grunert, with whom he was already acquainted from his time in Stuttgart.

Reiseführer, je, 80 x 48 cm, Epoxid auf Leinwand, 1991-96, Installationsansicht MMKK, Klagenfurt, 2009

Using synthetic resin and pigment on canvas, Zimmermann repeatedly made over-sized pictures of school atlases, art publications, paperback classics, and travel guides. Although the motifs may appear familiar and banal, they exemplify our forms of knowledge acquisition and our desires that are stored, at least in parts, between book covers. The picture is thematized at the same time in relation to structure, text, mass goods and our perception in a specific contemporary-historical conglomeration. Questions of design are as much available for disposition as the economic social ensemble that is evoked, which addresses the pictures on the one hand, but also the books as well. With this extensive work series Zimmermann situates himself in the discourse reflecting on the conditions of art in general and its presentation in the exhibition space in particular.

Peter Zimmermann

It probably also goes back to these early days in Cologne that Peter Zimmermann moved into his atelier in the street Kamekestrasse near the city garden, where he still works today. Also the subsequent series of printed boxes and cartons and the poster series and exhibition displays were presumably conceived here as well. A path seemed to be predetermined and capable of development in various bifurcations. Zimmermann directed his focus to the sometimes diffuse relationship between text and image. To what extent could written, highly complex mental expressions be accommodated on sculptural or poster carrier media and how does the viewer deal with that? Can the printed, discursively sophisticated contents enhance the value of a conventional cardboard box or carton installation, and can one still follow a text, even if it stretches across an entire billboard in the form of the most diverse typographical arrangements? At which point does the thread break and the more casually superficial, purely visual view win out? Zimmermann subsequently pursued these questions in various exhibition contexts and presentation forms and conceived challenging displays that only looked at first glance like familiar advertising surfaces or collections of goods. When he set up a kind of fair booth under the title “Temporary Architecture / Presentation of Boxes” at the Aperto exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1993, Zimmermann gained international attention. “The boxing in of the world takes place first in thinking,” states one of the first sentences of a flyer that Zimmermann included with the work. Painting was completely left out with this installation; it evoked more a recollection of the sculptural arrangements of Warhol’s Brillo Boxes. What was clearly in the foreground was an engagement through the interaction with the system surrounding art production, such as the parameters of reception in the institutions or the audience. What it invoked were the potentials and boundaries of communication in the various areas of the art business, the media, of public space, or also the political field, and thus how connections are made and then interrupted again. This phase of work on the use of signs and spaces, on the conception of instruments and politics of representation all the way to reflection on the role or function of artists/authorship and networks, ultimately culminated in 1998 in a large-scale solo exhibition in the Kölnischer Kunstverein with the title “Eigentlich könnte alles auch anders sein” (“Actually everything could be different too”).

Again and to a greater degree, the question of authorship was negotiated here as well. As soon as certain formal questions were clarified or directions specified, Zimmermann withdrew from the processes and waited curiously for the results. Commissions were awarded, working processes delegated, and experts from various disciplines persuaded to come on board. Characteristically, Zimmermann and his wife Natalie Binczek published no classical exhibition catalogue, but a hefty reader instead, with numerous essays on the theme of contingency. The exhibition and catalogue made it clear that there was always also a playful note to Zimmermann’s engagement with the art business, along with the philosophical approach.

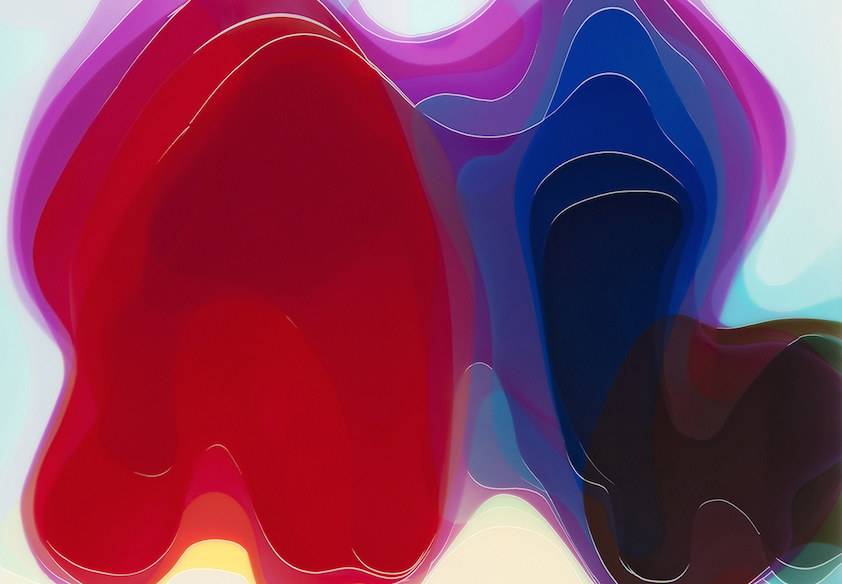

Some time before this exhibition in Cologne it was already evident that the use of text and image processing computer programs formed not only the material and tools, but increasingly also the theme of Zimmermann’s work. Another form of networked structures along with the circle of people involved was thus invoked and was to prove definitive for the further course of his work. In contrast with discourse networks, networked computer capacities consequently came more and more into focus. What was crucial was less the well measured, balancing exchange of thoughts, but rather the decision of a machine between 0 and 1. This was accompanied by a renewed and massive turn to opulent painting. Everything could really be completely different as well – the motto of the exhibition thus indicated the emerging change of direction. This turnaround certainly resulted partly from the noted lack of consequences from the tremendous effort of the Cologne exhibition. Despite a quite remarkable international press response, the reception in Cologne remained more reserved. Zimmermann’s new high gloss pictures subsequently conquered major and important exhibition institutions around the world, but the resonance in the Rhineland and especially in Cologne remained largely lacking. Zimmermann therefore turned increasingly to a practice of painting that consistently faced the challenges of new media techniques, both making playful use of them and yet also theoretically querying their potential art historical references and constructively testing them at the same time. This resulted in abstract images on making pictures in the age of digital reproduction.

However, Zimmermann’s stance on the question of authorship remained ambivalent. The starting point was excerpts from his own older works, for instance, or image material from the Internet, found image media or film stills, collected and thematically archived in personal image directories. After further distorting it with Photoshop, Zimmermann finally printed an aesthetically satisfactory result on a transparency and projected it onto a canvas. After the outlines were marked, the image was poured onto the canvas laid flat with epoxy resin. Over the years he was able to increasingly refine and perfect this procedure. Sculptural forms and gigantic floor, wall or ceiling installations were meanwhile also created in an additional large work hall in Ehrenfeld together with a constantly growing staff. The circle of assistants was partly recruited from former students of the Cologne Media College, where Zimmermann held a professorship from 2002 to 2007.

The still conceptual derivation of the images is no longer to be seen in the results. The sometimes strongly colored high gloss surfaces occasionally recall references from abstract and informal painting, and psychedelic impressions of a 70s flair cannot be dismissed, but what is clear in any case is the orientation to the omnipresent, seductive, glowing presence of high-resolution screens of all kinds. For the viewer the images are like looking at an over-sized plasma screen. Through a semi-transparent overlay of various color layers or merging forms, sometimes a kind of 3D appearance is created as well. Even though they are still and fixed, the images still convey the process of their creation from a flow of movement. Following one of Zimmermann’s favorite ideas, these could be pictures that paint themselves.

This measuring of himself against the most up-to-date media-technology achievements in rendering images has recently taken another volt. Zimmermann makes use of programs for processing image files on smartphones and mobile phones. Pictures taken with a mobile phone can be edited by simply pressing a button and suddenly look “as though painted”. A selfie can be transformed in seconds into an impressionist or expressionist portrait. Zimmermann uses this technological possibility and applies it to motifs from his collected pool of images. For this, however, he makes use of brush and pallet in a classical manner and transfers the abstract, “manipulated” images to canvas in painstaking detail. The term “handmade modernism” once coined by the theorist Hanrou Hou seems to apply to Zimmermann’s practice, as he imbues a genuinely handmade product with the mark of industrial perfection, which in turn imitates the handmade. Of course, “handmade modernism” does not mean the tinkering imitation of already existent technologies here, but rather perhaps also the craftsmanship anticipation of technical solutions as yet to be found for unresolved problems of society. For the historical alteration of technical standards and formats, in the course of which a new kind of visual industry has emerged due to computerization and miniaturization, has certainly led, to a significant degree, to a further destabilization of the idea of what it means to be a visual artist today. Zimmermann still continues to face this question, which is certainly to be counted among the continuities that permeate his artistic practice through all its modifications from the beginning. With Zimmermann’s highly reflexive approach throughout the course of his career, it is possible that a moment of critical potential has gone missing. A turn toward the aestheticization of concurrence may be conjectured, but that is certainly an abridged description of Zimmermann’s complex development, as it largely leaves out that a pleasurable way of dealing with colors and forms can certainly be counted as a gain. Artists as producers have always been dependent on the system in which they are interwoven and on the specific, not only historically contingent forms of address and reception. Reformulating or newly formulating the author or artist function therefore also entails ever new modes of viewing or also, perhaps in conjunction with this, an exchange of audience classes, which is at the same time an imaginary commensurability with the unknown. Networks of all kinds have to be developed here and can be used to compare and convey practice and theory. Whether a balance of theory and practice will be possible in Peter Zimmermann’s work in the foreseeable future in Cologne, is a question that must remain open for the time being. In the coming year, in any case, a major survey show will be starting first in Freiburg. A well intentioned tip thus suggests to the Rhineland exhibition institutions that they should not miss this opportunity.