“Weather is a Third to Place and Time”

Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Poetry of Landscape by Charlotte Desaga. Little Sparta, Stonypath, Dunsyre, Scottland & Ian Hamilton Finlay Park, Grevenbroich, Germany

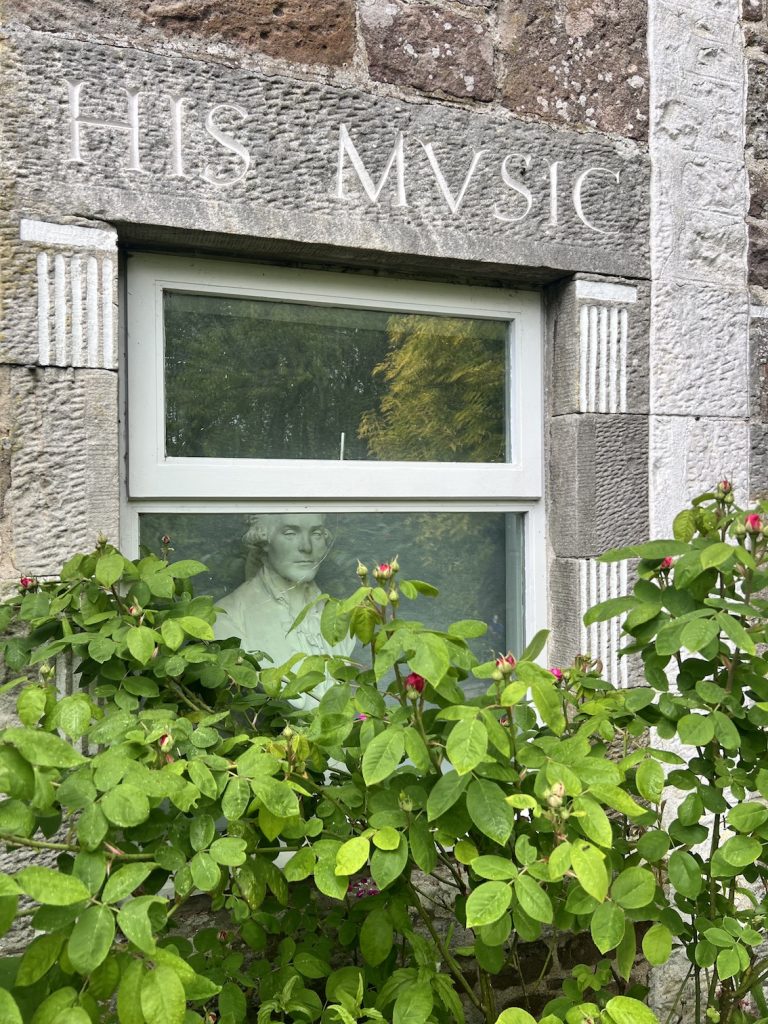

In the quiet hills of South Lanarkshire, Scotland, an artistic vision unfolds in a garden known for its intellectual charge. This is Little Sparta, the life’s work of Ian Hamilton Finlay.

The Scottish artist began his career as a poet and became known in the 1960s for pioneering concrete poetry in Britain. His early work explored the relationship between form and meaning through the typographic arrangement of words on the page. He maintained a vivid exchange with fellow poets, including the American Robert Lax and the Austrian Ernst Jandl, with whom he shared an intense correspondence. Though their approaches differed greatly, they were united by a common mindset: they understood the poem as a visual and acoustic object that communicates primarily through its structure. Finlay’s artistic evolution took a radical turn in 1966, when he moved to a remote farmstead called Stonypath. Over the years, he transformed the rugged landscape into a cultivated environment where poetic thought was woven directly into the land.

By the early 1980s, Finlay had rechristened the garden Little Sparta – a name deliberately chosen to contrast with Edinburgh’s classical nickname, the “Athens of the North.” This renaming reflected Finlay’s conviction that art should be active and combative, not merely passive or ornamental. The choice was likely also inspired by the myth of ancient Sparta: People who saw themselves as guardians of order, bound by discipline and deeply rooted in the land. The terms laconic and spartan – both stemming from the same geographical origin Laconia, a region in the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula in ancient Greece with Sparta as its most famous city – resonate broadly with Finlay’s artistic ethos: austere, restrained, and charged with quiet intensity.

At the heart of Little Sparta is the idea that the garden is not merely a collection of plants or decorative objects but a structured space for philosophical engagement. It became his platform, his playground, for visual poetry and sculptural interventions that explored themes ranging from mythology, classical philosophy and revolutionary politics to maritime history and the natural world, blending aesthetic beauty with critical thought. One of his lifelong artistic fascinations lay in the intersection of aesthetics and politics. He viewed revolution – particularly the French Revolution and its Jacobin period – as a complex phenomenon, embodying both utopian ideals and violent realities.

More than 275 works are thoughtfully integrated across the site, each positioned to engage with its natural surroundings. Many are modest in scale, partly concealed by vegetation or blending into the landscape. Rather than standing as isolated sculptures, these pieces form part of a larger poetic composition. They include inscribed stones, constructed temples, architectural follies, and symbolic arrangements.

The artist approached the garden conceptually as a language system, one that unfolds over time and space. As you walk its winding paths, you encounter texts embedded in a cultivated landscape – brief phrases or classical references that play off the forms and moods of the environment. The experience is dynamic, changing with the light, weather, and seasons.

“Weather is a third to place and time” Ian Hamilton Finlayonce remarked. During my recent visit to the park, this concept revealed itself with striking clarity. Over the course of just three hours, the weather shifted from rain to cold, from wind to sudden warmth, and finally to bursts of sunshine. Each change transformed the garden’s atmosphere, altering light, mood, and perception. In Finlay’s world, weather is not merely background – it is an essential, dynamic element that interacts with location and time to shape intensely how we see, feel, and understand a place. At Little Sparta, this triad of time, place, and weather isn’t theoretical – it comes vividly to life.

Although nature plays a central role, Little Sparta is not a wild or organic place at all. Every hedge, water feature, and inscription is positioned to serve Finlay’s conceptual purpose. Even the fencing and grass lines appear carefully aligned, reinforcing a sense of order and direction.

The park layout seems designed to encourage both movement and contemplation. Interestingly, however, there isn’t a single bench to sit on, to pause, or reflect. It’s as if the park invites you in – but subtly suggests you shouldn’t linger too long. This sense of deliberate distance echoes a sentiment Ian Hamilton Finlay once expressed in a letter to his art historian friend Stephen Bann with whom he maintained an intense correspondence over half a century: “I am not sure if I really feel very keen on this idea of ‘involving’ people. In works of art or poetry. It’s a wee bit like hitting them on the head, and saying, there now, you are involved. It makes me want to INVOLVE them back. A coolness is nicer. Not a coldness but a respectful distance.” That respectful distance still echoes throughout the park. Exploring it doesn’t strike with emotional depth; rather, it creates a composed, intellectual engagement. Terraces lead to glades, pathways open into groves, and sudden visual alignments reveal hidden texts or sculptures. These transitions foster a narrative rhythm, guiding through ideas rather than emotions. As Finlay reflected in another moment of self-awareness, “I was greatly perplexed as to why Stonypath did not have a garden-y garden… and I eventually realized that it was the lack of enclosed verticals – a situation we are solely remedying…” His eventual introduction of structures like trellises and sundials brought subtle shifts in spatial definition, but never at the expense of that cool, deliberate reserve.

Thematically, the works in Little Sparta often engage with conflict. Cultural, historical, or personal. Finlay’s use of symbols such as guillotines, warships, and revolutionary mottos challenges traditional associations with gardens as places of peace and retreat. Instead, Little Sparta becomes a site of intellectual resistance. Finlay viewed the act of gardening itself as a form of engagement with ideas: a philosophical activity rather than a passive pastime.

This conceptual depth often placed the artist at odds with institutions. His disputes with local planning authorities over the classification of structures in the garden became widely known and were woven into his artistic narrative. For Finlay, these bureaucratic battles were not just obstacles but integral to the work itself – an extension of the themes of power, order, and rebellion explored throughout the garden.

Finlay’s artistic language did not remain confined to Scotland. His ideas found resonance across Europe, and in 1995 a significant project was realized in Grevenbroich, Germany. There, a public park was created in homage to his vision. The Ian Hamilton Finlay Park reflects the same integration of landscape, poetry, and sculptural form found in Little Sparta. Situated in an urban environment, the Grevenbroich park adapts Finlay’s principles to a new context, offering audiences a space where art and environment merge to stimulate reflection.

Though different in scale and setting, the Grevenbroich project demonstrates how Finlay’s work transcends geography. His exploration of the garden as a medium – a place where nature, culture, and language meet – resonates universally. Both sites invite visitors to read the landscape as they would a poem, deciphering layers of reference and suggestion.

Finlay’s approach was collaborative as well as conceptual. He worked with craftsmen, designers, and stonemasons to realize his ideas with precision. Typography, materials, and positioning were essential to the impact of each piece. The result is a body of work that, while rooted in place, speaks across disciplines – literature, visual art, architecture, and philosophy.

Today, Little Sparta is preserved and maintained by the Little Sparta Trust. The garden is open to the public during the summer months, allowing for the fullest experience of its interplay between text, form, and nature. As it is Finlay’s centenary in 2025, interest in his work is being revived through exhibitions and scholarly attention. A series of exhibitions under the title Fragments is planned across major cities, highlighting the continued relevance of his practice.

What makes Finlay’s work so enduring is its quiet intensity. It demands more than casual viewing; it requires time, attention, and thought. The viewer is not just a spectator but a reader and participant in a poetic dialogue with place. Sometimes cryptic or hard to access, it remains very independent in its own right. In an age dominated by rapid consumption and digital distraction, Finlay’s work is the opposite, it invites slowness and depth.

His art reminds us that meaning can be embedded in the landscape, that a garden can be a space for ideas as much as for beauty. In both Little Sparta and Grevenbroich, the poetic and the physical are intertwined, forming a living testament to an artist who saw the garden not just as nature tamed, but as culture in bloom.

Article image: Ian Hamilton Finlay “Little Sparta”, Stonypath, Dunsyre, Scottland, Foto©: Charlotte Desaga