Banu Cennetoğlu

/ EN /

“I know very well, but nevertheless”. An interview on the occasion of her current show at Bonner Kunstverein (13.11.2015 – 17.01.2016). By Annika Turkowski.

News. Paper. News on paper. Newspaper! What constitutes knowledge, once it is broken down to a single sentence or a mere single word? What happens to a piece of news, once it has been collected, displayed and republished? Is it still legible? How relevant does it remain? In her first solo exhibition in Germany at the Bonner Kunstverein, the Turkish artist Banu Cennetoğlu explores language, its continuous dissemination as information and the potential value attached to it.

Annika Turkowski: You are currently showing your latest work at the Bonner Kunstverein. This is also your first solo show in Germany. How did the special structure of this kind of institution play a role in that?

Banu Cennetoğlu: As far as my experience goes, the Kunstverein is very specific because of the history of Bonn itself and its previous political function as well as its reputation and fame. Today everything in the city looks like it’s displaced in a way. In terms of where the Kunstverein is situated for example, the neighborhood, the potential audience that comes with it, but also the constructed audience.

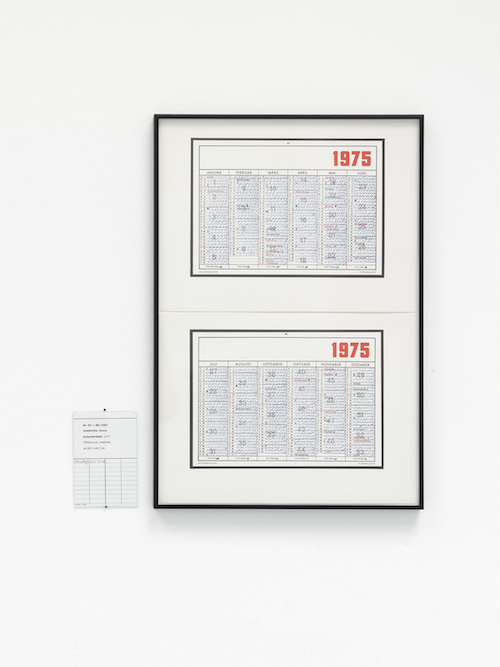

For me it was really interesting and also fascinating to work with the Artothek, through which the whole collection of the Bonner Kunstverein is available. Thinking about distribution, dissemination possibilities, value and the market, in relation to the original purpose of the Kunstverein from fifty years ago when it was founded; its motif of a democratic distribution of art. So that’s why I tried to work on different levels, with different ingredients of the institution.

Banu Cennetoğlu, My Temporary Darboven Nr. 87+88 / 1987: Kalenderblatt, 1975 , Offsetdruck, zweiteilig, Je 29,7 x 40,7 cm, Collection Artothek, Bonner Kunstverein, Courtesy the artist and Bonner Kunstverein, photo: Simon Vogel

One of your works will also be on public display in Bonn in January, right?

Yes, The List. But I don’t consider it an art piece, because I don’t edition it, I don’t commercialize it, and I don’t sign it. And there is no authorship. I mean, I have a rather large emotional relationship with the whole content but it is more about making the content visible through many different levels of collaboration. I guess you can call it an intervention. But what it actually is: It’s a document, compiled and upgraded by a NGO based in Amsterdam called UNITED for Intercultural Action, or short UNITED. It’s a document* which compiles the information of people who died within the borders of Europe. When they were trying to cross the borders, or when they were already within the borders, in detention centers, refugee camps, etc. UNITED started compiling it in 1993 and tries to update it every year. But of course, unfortunately, they are not able to update it as they used to because of the intensity of what is happening since January 2015.

The List, Basel, 2011

So you have been working with the document before?

I started working with it in 2003 and managed to put it on display for the first time in 2006 in Amsterdam. From that time on, I tried to continue displaying it depending on the circumstances. I have used different platforms, like integrating it in my exhibitions be it a personal show or a Biennial, networks, logistics, budgets, partners, institutions, allies, all sorts of collaborative elements. I try to increase the visibility of this document through public channels such as billboards or newspapers.

This summer, after the invitation of YAMA, a public screen for non-commercial works on the rooftop of the Mamara Pera hotel, it came to a breaking point and for the first time I interfered radically with the format. In collaboration with another artist/ friend, Nihan Somay, we edited the whole content, transferring the entire content of the document, around 1000 pages A4, into a video format. At the end it was a video documentation of 360 hours. Every night, form sunset to sunrise, the whole document was screened at YAMA. The following day it was continued from where it stopped the night before, so at the end it was screened for 30 days.

I am quiet specific, that The List should be shown in a negotiated space. It is not a guerilla-style, copy-paste hanging of posters around the city without knowing if they are going to stay or not. We always try to negotiate as much as we can: the duration, the format, the budget, the place, the sponsorship if needed etc.

So now for two weeks in January 2016 The List will be hung as 200 posters in A0 format throughout the city of Bonn.

How important is the editing process in The List? You mentioned that for specific times you eliminate this editing process completely but at other times it seems to be crucial.

Until this summer, I never edited the PDF document provided by UNITED. If necessary it was translated to one of the native languages of the local context, always respecting the original document. If it was shown in Bulgaria, it was translated to Bulgarian for example. So it was never edited in terms of content. But this summer, when we decompressed the file to single words for the display in Istanbul, each word started to mean something else. The relationship between the reader and the content and also between the editor and the document changed. Every word was on display for approximately 2,5 seconds. The visibility and perception of the content were changed drastically. Suddenly, things we never talked about became crucial. For example, when we were not in agreement with the political position that a specific wording could generate, such as choosing “enclave” over “Spanish land” for Melilla and Ceuta, “transgender over man” or “Kurdistan” over “Kurdish land in Turkey”. For the first time our own political position began occupying the content of the document, so we decided to edit certain words.

The List, YAMA, The Mamara Pera Hotel, Istanbul, August 27 to September 26 2015

How does this project relate to the other works you are currently showing in Bonn?

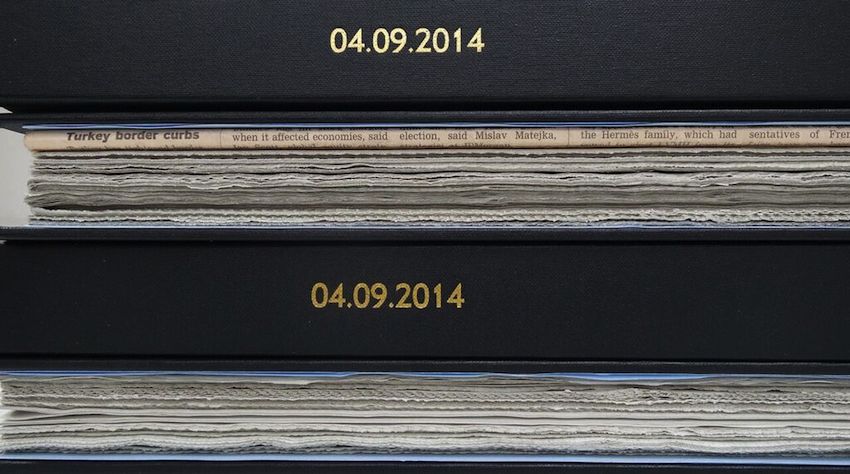

My work deals a lot with listings, collections, rearrangements, archives in many different ways. The main piece of this exhibition is a continuation of a work that I began in 2010 in Turkey. It aims to compile the entirety of daily newspapers printed on one day, when the entirety is inevitably still a fragment (a fragment of 1249 daily papers printed in German context). I started it five years ago with newspapers printed in Turkey, as an attempt to see the value of a piece of information. I was interested in comparing this value in different newspaper ideologies. To see how a newspaper chooses to place a piece of information, in respect to the layout, like how big, where, in which color or whether maybe to leave out completely. I was interested in the economy of space within a newspaper, if you will. The money value, since it is classified how much one pays for each space in a paper, but also the symbolic value of this occupation.

The value of a piece of information was one side, the other side was the nature of the newspaper itself. It is not supposed to stay and it won’t. It requires very specific conditions to do so. Also in regard to the relevancy of the content, because it is a very time specific medium. Unless you are an archivist, then maybe…

Banu Cennetoğlu, 04.09.2014, 2014, Tages- und Wochenzeitungen (United Kingdom), 46 Buchbände (Hardcover), Photo: Banu Cennetoğlu, Courtesy: Banu Cennetoğlu, Rodeo Gallery

What is the incentive to collect the news coverage of a single day in a country? Where does the appeal lie for you?

I am interested in the specific fragmentation and juxtaposition of an archive. You can collect and build an archive based on a specific newspaper or important date. But you can also sequence and juxtapose information in an unconventional way. The newspapers I collect are forced to become part of a large collection. They were not naturally part of one. They do not really belong together. I am intrigued by this very subjective, biased, but not activated composition.

My next question is about display, taking the work we just spoke about, the newspaper archive, as an example. To me it feels like it is an important aspect in your installations.

Yes, definitely.

I always conceive your settings as very minimal, very cool, almost unwelcoming, if I might say so.

Cold you mean?

Banu Cennetoğlu, Catalog 2009, Artist’s Book, 912 pages, 21 x 28 cm, offset printing, Ed.: 150, 53rd Venice Biennale, The Pavillon of Turkey, 2009

Yes. What does that give to the work presented?

The display of my work is very site-specific. Of course I have, like all of us, a certain kind of aesthetic, but for me there is one main decision to make when I make a presentation for this work: Am I inviting people to sit or to stand?

Because both are completely different ways of dealing with and perceiving information. I mean, do I intend to turn an exhibition space into a library situation? Which it is not! An exhibition venue is not a library. Do I accept this as it is? Or do I try to convert it? That depends on the conditions and the given structures. In Cyprus for example, it was only one table, because there are only 32 papers printed on the island in Greek, English and Turkish. Bound in 3 volumes, they were on a single table with three chairs. The table was borrowed from the art center. It was a group show for six months and it worked as a place to just scan an archive. Aesthetically there was nothing special about it. Still, people were going through it and when the books came back, they were almost torn. Obviously this becomes part of the work too. I leave them as they are.

At the Kunstverein it is about inviting people for a shorter engagement with the material.

Well, especially considering the size of the Kunstverein…

Exactly. The Kunstverein is very specific, a very difficult space…It’s too large [laughs]. I thought it would be amazing to cut the space diagonally in half. That way I could display all of the 70 volumes at once. Considering the scale of the archive, there will be few times I will be able to show it as such. This also had a certain kind of violence and harshness to it. Maybe that is where you felt the coldness. This kind of display was also interesting in terms of the construction of this kind of information, that we call “legitimate knowledge”. A concept I highly doubt. I think the rigidity of my display plays a part in that. Rather than making a comfortable, cozy library with warm yellow lights, I wanted something unrelenting.

You said it is very site-specific, but did you do something that was the total opposite of this kind of display somewhere else? Something that was kind of cozy…

I guess the display in Cyprus was maybe the most casual, if you will. Also, the show in Amman, Jordan in 2011. But that was different in content and scope, because the newspaper archive there included different countries and languages, rather than just one country. The newspaper archive in the Arabic speaking countries was more an investigation of the potential and pertinence of artistic practice in times of crisis. At the same time the Tahrir square events in Cairo were happening and the atmosphere was filled with violence, I mean it still is, but that was the beginning of everything. So while we were discussing this, there was fire out there.

Banu Cennetoğlu, ICHWEISSZWARABERDENNOCH, 2015, 23 foil balloons inflated with helium gas and installed on Monday, 10th November 2015, Courtesy the artist and Bonner Kunstverein, photo: Simon Vogel

So the intention was to investigate one single day in this region and to see the state of mind of a place connected by the same language. It was a very difficult and long process. The aim wasn’t to collect all newspapers, just as many as possible from this particular context. The only criteria for choosing a paper were, that they should be daily and in Arabic. The ideology was irrelevant, as was the place selling the newspapers. The first time I showed the archive in the exhibition it was still in progress. They were not even bound. That was a very casual and improvised display. So I guess the display depends on the exhibition situation.

But in contrast, what I like very much at the Bonner Kunstverein, is the spatial interplay between this piece and another new piece. They came together through the famous code of Octave Mannoni* „Je sais bien, mais quad même“/ „I know very well, but nevertheless“, which is spelled in German – ICHWEISSZWARABERDENNOCH – in the show with foil helium balloons. This is a totally new medium for me. Filled with helium gas and set up without any support structure but the architecture of the space, they are rearranging themselves every day. Each letter has a different relationship with the helium, with the room temperature, with the letter next to it, the way they are leaning to each other. I like that piece very much. I see it in relation and opposition to the rigidity and coolness of the harsh structure of the „legitimate information“ we spoke of before. I see both pieces together. Both try to deal with language and the perception of information. But they do that in very different ways.

What does this sentence mean to you? – „I know very well, but nevertheless“

I think that knowledge does not necessarily trigger an action. It might disappear eventually. Just like the letters: Now they are bold and beautiful but eventually they will become something else. In a way, it is about the over-reliance on the word itself. What happens if it is re-contextualized and de-contextualized? What is the potential of wording basically.

Banu Cennetoğlu, photo by Merve Caglar

Speaking about spatial interplay, you also changed the entrance situation of the Kunstverein.

Yes. The whole show was conceived on different levels and in different parts of the institution and the Artothek or its local context, the city. I worked with small gestures. Rather than just using the space as a container for displaying works, I tried more to “contaminate” it. For example, I changed the lights of the entrance to the Kunstverein. There are those two huge structures holding 16 bright white neon lights. For the duration of the exhibition they glow in red, yellow and green colors. For centuries, these colors have stood in the Kurdish tradition. Throughout the history of Turkey and the struggle with the Kurdish community, those three colors became this very violent symbol. At some point, in the 1990’s, the Turkish government wanted to suppress the use of these colors, like changing the traffic lights from green to blue in Kurdistan. More recently, just before the November elections, people were taken under arrest for wearing garments or scarfs with those three colors. I mean we are talking about three basic colors. You can imagine the scale of intolerance and hate here…So for me, this piece was a very small gesture towards the Kurdish community living in the area around the Kunstverein. Especially following the recent extreme violence towards the community in Turkey.

Banu Cennetoğlu, „a problematic“ triad : yellow red green, 2015, 32 flourescent lamps in yellow, red and green, Courtesy the artist and Bonner Kunstverein, photo: Simon Vogel

An invitation to the Kunstverein, so to speak?

Exactly. And apparently it also works. So I was told.

Thank you very much for this interview!

*http://www.the-list.info/en/list-istanbul-yama.php

http://www.unitedagainstracism.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Listofdeaths22394June15.pdf

Article image: Banu Cennetoğlu, 11.08.2015, 2015, newspapers printed in Germany dated 11.08.2015, 70 volumes (hardcover), Courtesy the artist and Bonner Kunstverein, photo: Simon Vogel