New Column

/ DE /

by the artist Claus Richter

Hello and welcome to the “Richter Collection”, the new column in the artblogcologne. I came to Cologne about four years ago, and in an exorbitantly large coach I brought with me one hundred and seventy-three trunks with silver clasps, filled with old books, toys and other delightful artifacts. A seven-and-a-half-tonner, as one might say. As this has grown over the past four years by probably another two tons, it is gradually becoming the “Richter Collection”. Now every month one or two of these most enchanting things will be presented here, which I, at least, find particularly charming.

Today we start nostalgically with two things, each about a hundred years old, a periodical and a portfolio with prints:

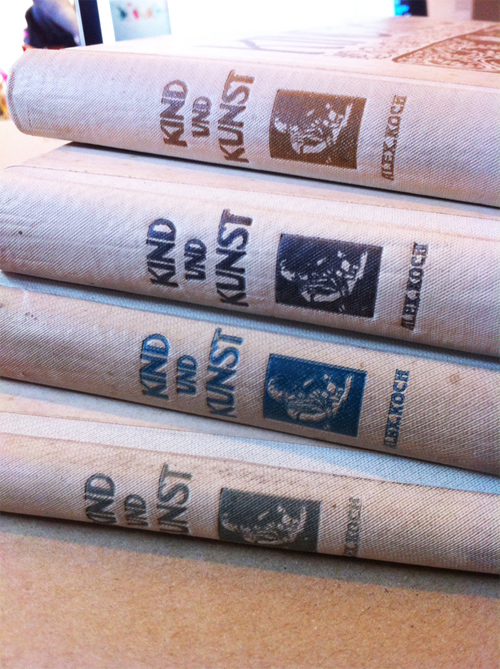

“Kind und Kunst” (published by Alexander Koch Verlag Darmstadt 1904-1905)

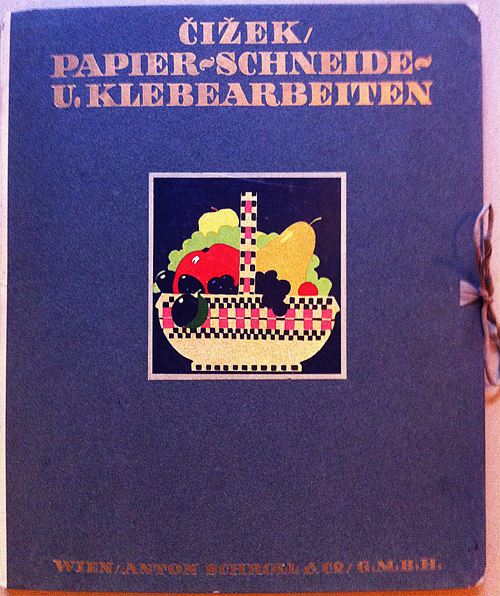

“Papier-Schneide- und Klebearbeiten. Ihre technischen Grundlagen und ihre erzieherische Bedeutung”, published by Franz Cizek, Vienna 1914

Let’s start with the periodical “Kind und Kunst” (“Child and Art”), presented by the publisher Alexander Koch from Darmstadt between 1904 and 1905. Just like the periodical “Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration” (“German Art and Decoration”), which was also published by Koch, “Kind und Kunst” is addressed to the genteel upper class. Several months ago I had the good fortune of acquiring all the editions of this periodical in four bound books, through which I have been continually and genteelly browsing since then. As art and decoration periodicals flourished around the turn of the century, British publications such as the “Yellow Book” or the short-lived, but legendary “Savoy” were models for Alexander Koch’s Darmstadt publications. Things were buzzing everywhere, as it seems at least in retrospect. Just like the flamboyantly decadent grotesqueries of Beardley & Co, the reform movement was directed against the moral constraints of the world view of that era. Everything was to become different: sex, art, thinking, living, and of course education.

What a good idea! The Swedish progressive educator Ellen Key wrote her book “The Century of the Child” in 1903, a book that is horrifying to read today, as Ms. Key actually proposes euthanasia for handicapped children and abstinence for alcoholics and those with hereditary diseases, but on the other hand, and in this it is a fantastic book, she also argues vehemently and convincingly against the paternalism, violence and infantilization that most children were exposed to up until that time. Although Rousseau had already taken up the defense of the child as a being with equal rights in “Emile” in 1762, it was not until the turn of the century that there was a broader discussion of childhood as a phase of life with an intrinsic value and that perhaps small people should not be patronized and beaten black and blue wherever possible. All of this did not happen from one day to the next, and “Kind und Kunst” was, as previously mentioned, a paper for the upper class, which was probably composed then as now, however, of nice people and not-so-nice people. I imagine that “Kind und Kunst” was likely to be read by nice rich people; at least in my edition there is a card, as a forgotten bookmark, from a presumably older aristocratic lady, who may have pleased her grandchildren then with fat kisses and amusing artistic wooden figures, so that they later grew up to become sincere and genuinely good patrons of art and humanism. Like all reform arts of the time, the attempt to implement an everyday life with all the newly envisioned beauties ultimately failed due to the high costs of production. Even magnificent and immensely wealthy patrons like Fritz Wärndorfer, who supported the Wiener Werkstätte beginning in 1902, went completely bankrupt with them following rough times.

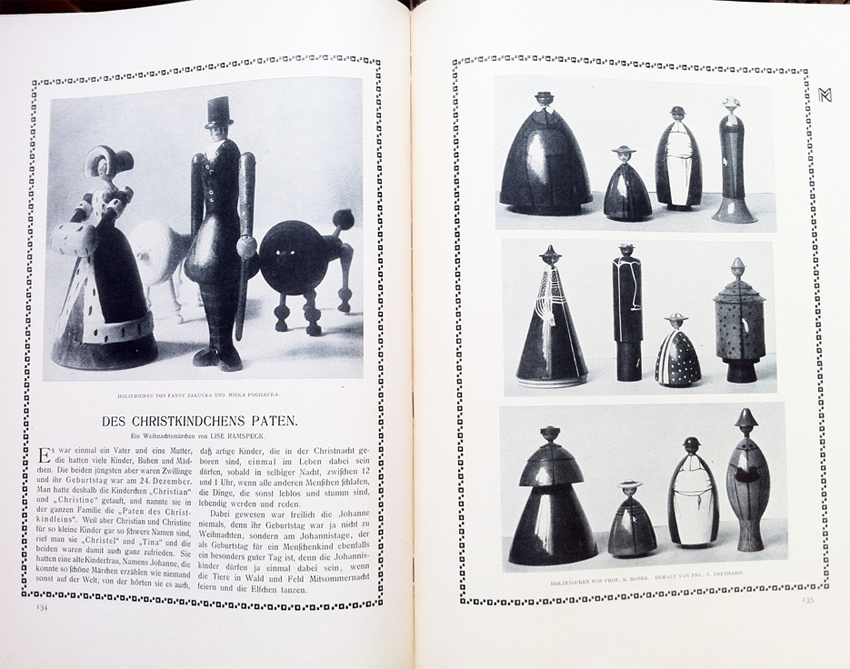

Many of the designs were only produced in very small editions, some of them remain forever designs; the Dresden Werkstätte Hellerau and the Wiener Werkstätte brought some toys into production, but here too, lack of money and high production costs caused the ultimate demise of production, so that even these objects are only to be found occasionally in museums.

Anyone who enjoys artistic toys from the turn of the century as much as I do does not need to go directly to the doctor, but only to jump on the next train to Nuremberg, where the toy museum shows incredibly beautiful single designs from that era on the ground floor. Today the Dresden Werkstätte are again producing several selected replicas by Richard Kuöhl, Otto Froebel, Hermann Urban and Richard Riemerschmid.

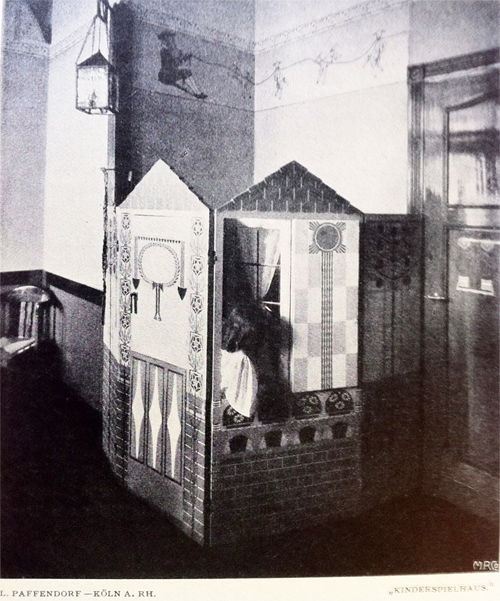

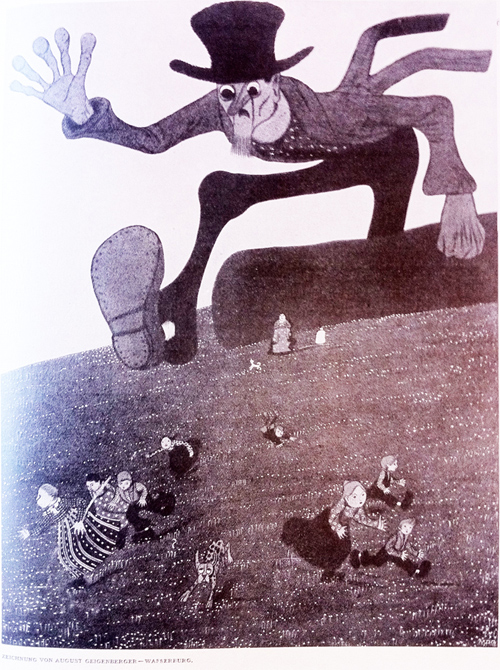

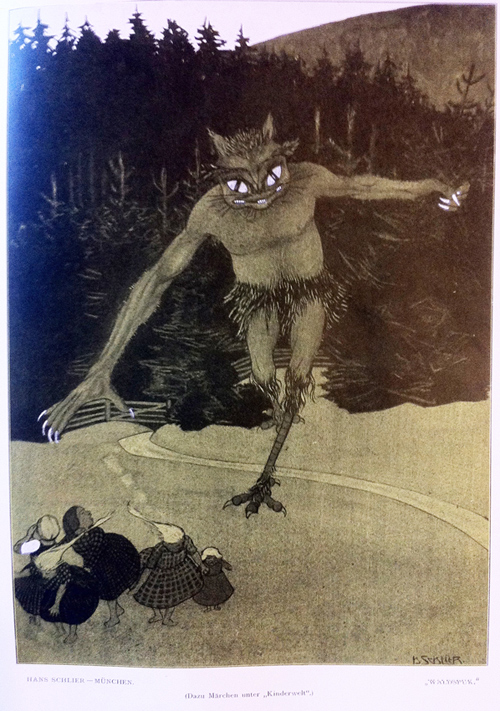

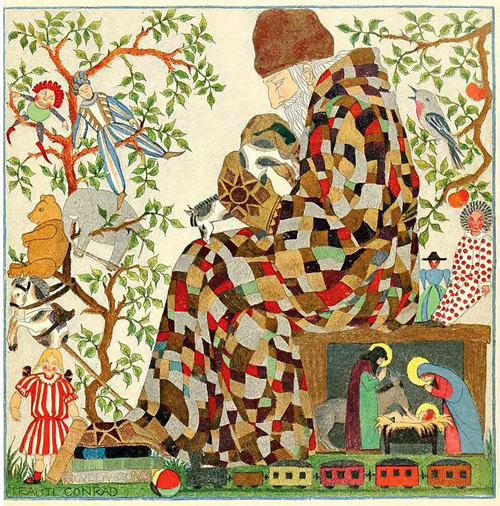

In “Kind und Kunst”, the “who’s who” of designers at the time from the aforementioned Werkstätten mingle with artists now forgotten. Koloman Moser designed wonderful cities of wood, Carl-Otto Czeschka shows wooden knights that seem to have sprung directly from his illustrations, Heinrich Vogeler illustrates the first summer day in the life of a small baby, Dagobert Peche’s opulent toy cities would be the perfect home for the funny wooden figures presented by the Dresden Werkstätte; on the next page, followed by the darkly magical illustrations by the brilliant Ivan Bilibin, these wooden figures might risk a little dance with the grotesque toy designs by the Kleinhempel siblings, just like the children in the article on the children’s dance group of the revolutionary dance educator Emile Jaques-Dalcroze.

Half of “Kind und Kunst” is a kind of advertisement for the newest artistic toys, but the other half reports in editorials on the most recent ideas in progressive education. Children dance there in billowing reformed clothing to the new ideas of the aforementioned Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, who later taught dancers like Mary Wigman and whose class also included Marie Rambert, who helped Nijinsky to choreograph “Le Sacre du Printemps”. In addition, Jaques-Dalcroze naturally also spent half a year at the legendary Monte Verita. All of this is dreadfully elitist, of course, but I find it better to entrust a wealthy child to the hands of a revolutionary than to drum ten foreign languages and economics into him, while the others may be playing outside in the dirt. Children’s drawings are published in “Kind und Kunst”, and there are regular articles about the children’s art classes of the world, in which children (we will come back to this in more detail later) are allowed to freely and easily paint, do crafts and build things and proudly present their work. Browsing through the pages, one discovers art that can be fun and educational, is not ashamed of its decorative and playful character, and is certainly not afraid of human origins.

I don’t know what a periodical like this could look like today. The “Kind und Kunst” photo series about “The Naked Child in Nature” would probably no longer be possible today, as I can already hear several very, very concerned mothers calling for the death penalty.

I still find the toys, spatial designs and many of the illustrations from “Kind und Kunst” enticingly beautiful today. By that I mean neither slick kitsch nor any “designer style”, nor is it a matter of naively excluding tensions and problems, but it is an attempt to simply make the best of things. An endeavor, a task. People thought: beautiful things make fine people. On this, Karl Staudinger wrote in 1923 in his book “Entschiedene Schulreform – Kind und Spielzeug” (“Definitive School Reform – Child and Toys”) the following: “Not everyone’s children have a golden cradle between palace walls. Often they grow up in more than impoverished surroundings. Where then should they gain their first impressions of beauty, impressions that stay with them throughout their lives? Should one drag little ones into the museum and show them things alien to their lives, or should one wait until they see things later among those more fortunate, which arouse their envy without leaving them any enjoyment of use? Those who are less blessed with earthly goods must usually rely solely on inner joys. Yet the satisfied enjoyment of these must also first be learned, and the path to this leads through recognition of the beautiful. – This compensates for some hardships and woes, and he who has recognized beauty seeks it out and knows how to find it without first making up for it with gold. But that must first be learned. – In fact, all those who deal with artistic things are able to bear the dullness of everyday life better than some who are more fortuitous with a plainer occupation.”

This was the plan, but unfortunately it all turned out quite differently. After World War Two, the progressive ideas of reform did not reemerge until the late 1960s and early 1970s – I’ll just mention daycare facilities, Charles & Ray Eames, Sesame Street, Rappelkiste, alternative kindergartens.

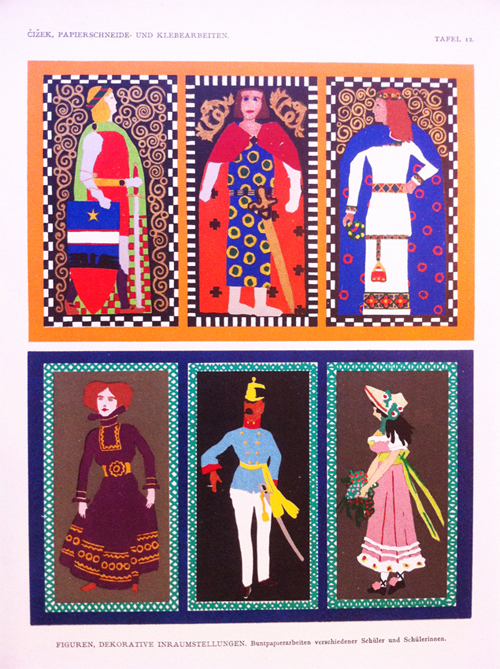

A kind of early alternative kindergarten with an orientation to art was already founded around the turn of the century by Franz Cizek, however. In Vienna he gathered children around him in his courses and allowed them to freely choose what they wanted to work on and with which materials. The results are still spectacular today. Therefore, the second object I will show is “Papier-Schneide- und Klebearbeiten. Ihre technische Grundlagen und ihre erzieherische Bedeutung” (Paper, Cutting and Glued Works. Their Technical Foundations and Their Educational Significance”), published by Cizek in 1914, here in the edition from 1916.

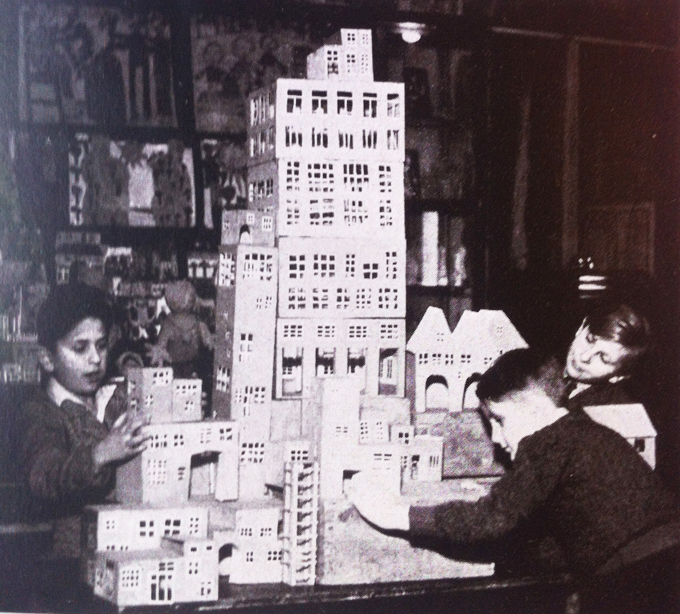

All the works in this portfolio are by children not older than the age of 14. When Cizek presented the first exhibitions with works by children in 1905, there were even petitions against this unbelievable impudence; the National Socialists closed Cizek’s school in 1939. This was no walk in the park, even though Cizek’s freethinking approach attracted considerable international attention. For example, none less than Edmund Dulac wrote the introduction to Cizek’s publication “Christmas Pictures by Children”, which was published as a book in 1922 and is so full of fantastic drawings that it is almost dizzying. In the courses the children often worked to music, and Cizek emphasized that he had no teaching method, but instead supported the children in finding form as an invisible teacher, so to speak. Sometimes themes were given, such as “The City” or “The Circus”, but often the children also worked completely freely. I must admit that I look at the artistry and sophistication of some works with a certain envy. But even scribbling and less developed fine motor skills were equally praised and promoted by Cizek. The point was not to form little artists, but rather to foster self-assurance and enjoyment. In this sense, the courses were specifically not “elite education”, a seal that some academies like to grant themselves today, but rather a sheltered space for playing and making things.

All of that was over a hundred years ago now, the world is different today, and since contemporary art repeatedly likes to pour old wine into new skins, it would be amusing to see a great reform revival break out now for a change (there have already been some relevant thematic exhibitions here and there, and quotations of image language and creative formation can also be found again and again among contemporary colleagues), but perhaps it is enough that it once existed. At least that. I browse through these books with a nostalgically misty-eyed expression and plan to design a series of children’s toys in 2014, which will unfortunately be so expensive to produce that they will bankrupt me and my gallery. “It’s better to be a flamboyant failure than any kind of benign success,” said Malcolm McLaren, and that is also what it says on his headstone. Someday I’m going to put flowers on his grave. Next month, something completely different. Until then I remain, with a graceful curtsy and a slightly coquette batting of the eyes, yours truly, Claus Richter