Kai Althoff

/ DE /

Outside and in the Midst of it All: A portrait by Sabine Elsa Müller

“But spirituality and adornment are no enemies, rather both are to discover their natural unification within the feeble attempt to make life bearable.”

The accompanying text that Kai Althoff used for his first solo show at Michael Werner in 2014, read like a manifesto that culminated in a call for balance between spirituality and decoration.

Just like spirituality, beautiful form, decoration is ascribed the ability to calm the soul—on an aesthetic level. Althoff sees his notion of the successful decoration of spaces, things, and surfaces realized in the “reflection of an approach to art in the homes of people with good taste and intellectual brilliance from times long past.” The interiors of a Florine Stettheimer come to mind, an early 20th century New York painter who held elegant salons for leading artists, art dealers, and collectors of the day.

Althoff transformed the spaces of the London branch of Galerie Werner, one of the global players on the art market, into just such a salon. With this individual show, the artist catapulted himself into the top league—of course not without referring to the upcoming retrospective planned for New York’s MoMA in 2016. But the view and access to the “hot goods”—the painting itself—were aggravated in that drapes of semi-transparent material were placed over the pictures, blocking a free view. In the midst of it all, mannequins as silent figures, draped in flowing cloth, quiet music (composed and sung by Kai Althoff) and small tables where one could sit as if one were supposed to feel at home.

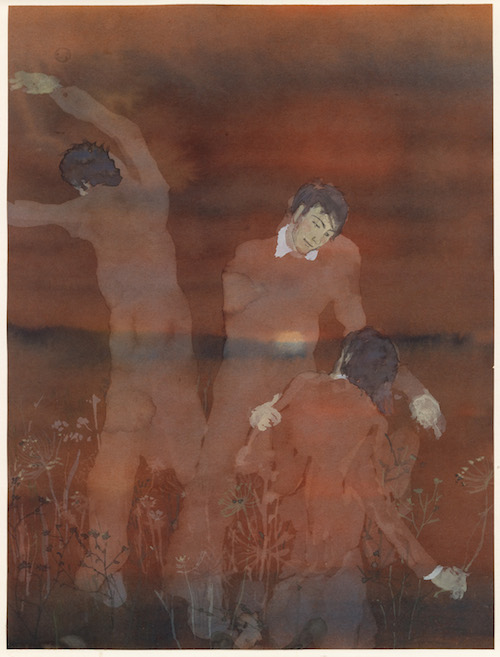

It seemed as if the decoration was intended to distract from the pictures themselves with their quiet scenes in earthy colors. Their casts were reduced to several people; often children or animals were the main figures. With very unusual picture formats, where there was scarcely a right angle, the pictures seemed to want to distance themselves from the clear classification as paintings. Instead, they nestled into the furnishings of a room cloaked in semi-darkness. They were there and at the same time resisted being viewed as much as they could. The lines separating beholder, producer, craftsmanship, and artifact became permeable, creating an intimacy in the space that let the commodity character of the paintings slip to the background for several moments.

Kai Althoff’s striking ambivalence vis-à-vis institutions and the market seems to be something of his trademark. When he declined participation in Documenta (13), the aritistic director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev exhibited the five-page, handwritten letter of refusal in a case as the only item on display in a huge hall. In this way, Althoff ultimately did participate in one of the most important exhibitions in the world, without delivering a single work. It is no surprise that doubts then were raised of whether he ever really meant his refusal seriously.

Born in Cologne in 1966, his artistic activity began in the late 1980s with a band. The band Workshop was not just characterized by the object character of the individual albums; what was important was the production process in the collective with varying memberships. This idea of a non-hierarchical art practice accessible to all beyond elitist high culture, beyond the realm of individual art geniuses, was widespread in the 1970s. As could be seen in the recent Sigmar Polke exhibition in Cologne, the playful and integrational approach to art were linked to great hopes in a transformation of society were linked. Beuys’ notion of “social sculpture” should be seen in this context.

Althoff maintained this attitude throughout the 1980s, a time in which the male-dominant artist cult came back into fashion with the “neue Wilden,” the “new wild” painters of German art. With the expansion of the concept of art, Althoff also linked the integration of bordering arts like music, poetry, theater, architecture, applied art, applied graphic design, and so on. His early exhibitions at the Cologne galleries Lukas & Hoffmann, Christian Nagel und Daniel Buchholz were marked by the great heterogeneity and the mixing of genres and seduced with literary titles such as Uwe: Auf guten Rat folgt Missetat, 1994, Bezirk der Widerrede, 1998, or Ein noch zu weiches Gewese der Urian Brüder, 2000. They evoke an imaginary space, that is by no means inferior to the space of association opened by the artifacts.

After 2000, he made a name for himself with large solo shows. After his 2004 exhibition at ICA Boston, a show followed at Kunsthalle Zurich in 2007 and in 2008 a comprehensive show at Vancouver Art Gallery. The latter, in its tripartite structure, showed Althoff’s various approaches, depending on his intention.

On the one hand, collaborations with artists and laypeople continued to have validity, just as did his interdisciplinary view of art. While in the exhibition catalogue he propagated the negation of art (“I do not think art exists even,” Kai Althoff & Jennifer M. Volland: In Conversation, Vancouver Art Gallery, 2008, 18) that sounds as if for him there is simply no difference between art and non-art.

In Vancouver, Althoff invited the young art school graduate Travis Joseph Meinolf from San Francisco to collaborate with him. Meinolf brought his own self-made looms to museums and galleries to recall the weaving of warming blankets as a valuable cultural ability. Althoff himself, using the pseudonym Joey Engelhardt, created drawings as decoration for the weaving course and created seating of white wooden furniture and glowing blue pillows for the workshop. The invented alter ego separated his product from the prominent artist personality and attributed it to a communal project.

Meinolf and his loom also played an important role in I Will Be the Last, a dance performance held on the opening day in Vancouver and for which later at the exhibition Not Yet Titled at Museum Ludwig an entire room was dedicated to showing a projection of the performance in original size. The floor of the projection space in Cologne was covered in the same white velour carpeting as the original setting of the performance, so that the lines separating the fictional and the real presence blurred. In I Will Be the Last amateur dancers present an Arcadian idyll in which the harmony of the community is threatened by a single person (Althoff), who is ultimately excluded from the group. The music, consisting of cymbal and computer sounds, was also by Kai Althoff, who has been making music since his youth. Together with ancient costumes and movements muted by the carpet, the sound level amplified the strangely engrossed tenor of this performance.

The second exhibition segment at Vancouver Art Gallery was curated by Jeff Wall. It showed a range of Althoff’s painting. These were the paintings that triggered the fascination among collectors for Althoff as an artist. With changing styles, reminiscent of early medieval frescoes or elaboration book illustrations, without seeming antiquated, they enchant with their precision and the ceremonial seriousness with which they illuminate their narrative subjects. They are the exact opposite of a collective product. Amazingly intimate and touching due to the style of painting, their expressive power, and to their complex content, these paintings are only conceivable as the result of a deep immersion in his own activity. In addition the artist genius comes into his own, a genius that is linked to others in collective works and in a certain sense is lost in them.

Seen in this way, Althoff’s sculptures and objects, that made up the third part of the exhibition, could be understood as a synthesis of these two counter poles, a celebration of subjective expression on the one hand, merging into the community on the other. One of these objects is the iron sculpture Untitled. This work also emerged as part of acollaboration, a collaboration between Aachen metalworker Michael Hammer with Kai Althoff, who provided the drawings for it. With dimensions of 3 x 3 x 2 meters it expands in the space, quite literally. Two overextended arms with balloon-like sleeves or arms swing out over a strangely rolled up figure up high. The head floats just above the ground, framed by a low construction of iron rods, half support, half cage. It is unclear whether at issue is a place of retreat for its own protection or an attempt at breaking out—probably both.

In 2013, a work by Althoff appeared in the new collection presentation by Philipp Kaiser at Museum Ludwig, Not Yet Titled: the already mentioned steel sculpture from Vancouver, for the support of which Kaiser was able to win over the Freunde des Wallraf-Richartz-Museum and Museum Ludwig. Gracious and elegant, characterized by formal perfection and yet open and permeable in everyway, the figure forged using armoring iron spanned a bridge from the Rhineland tradition of art to sculpture of the 21st century with linkages to Ewald Mataré and his southern portal of the Cologne Cathedral to the Cologne-New York avant-garde of the 1990s, of which the Cologne artist Althoff was a key figure.

Kai Althoff, Ohne Titel, 2008, Stahl, 279.4 x 318.8 x 205.4 cm, © Kai Althoff / Courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Kai Althoff had finally arrived in the museum to which he had been invited a good ten years ago by Kaspar König. But he rejected the invitation, just as he did Kathrin Rhomberg’s invitation to Kölnischer Kunstverein. He preferred to nest on the city margins at the Simultanhalle, the rehearsal stage for the new building of Museum Ludwig. With the escapistically biting overall installation Immo (2004) Althoff also took his leave from Cologne. New York, where he already achieved great international attention in 2001 with “Impulse” at Anton Kern Gallery at a participation one year later in Drawing Now: Eight Propositions at MoMA, now became the focus of his life. In Cologne, one was surprised by the huge limousines parked outside his exhibition in Chorweiler. The collectors were eager to get their hands on the Althoff originals, that were hidden between found pieces like pieces of clothing, posters, furniture, and old record player, and a much older baby carriage and the like. With the sale, the destruction of the total work of art, that Althoff understood “Immo” as, was accepted.

Kai Althoff “Immo” Simultanhalle, Köln, 2003

Such experiences might well have contributed to Kai Althoff’s distanced attitude to public attention. He participates in the exhibition business, infiltrating it with reformist models, but tries stubbornly to control the presentation of the work to the outside, for example, by own releasing illustrations in exchange for seeing the text written first. This could be understood as censorship, or as the attempt to protect the autonomy of the artistic statement by all means. As an author, this attitude is quite understandable, and can even be considered laudable, an offer of cooperation that does not exclude defining one’s own position in the economic system of art.